21 Jan 2014

For nearly all of us, I think, the words ‘war cemetery’ call up a very particular image to the mind. Row upon row of perfectly aligned pristine white headstones on a flat landscape stretching a huge distance; the graves separated by immaculately maintained grass and, here and there, individual floral tributes placed by the relatives of those who made the ultimate sacrifice in conflicts long ago.

Thanks to the dedication and hard work of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) who manage and maintain these places, the image is one of neatness, order and solemnity. In many cases, the sheer scale of the cemetery making an eloquent point in itself.

Belgian MP Joëlle Kapompole showing me a painting of British soldiers at the Battle of Mons.

Calm and Reflection

Saint Symphorien military cemetery near Mons in Belgium isn’t like that. To begin with it’s quite small, containing the final resting place of just over 500 soldiers, divided roughly equally between German and Commonwealth combatants from the First World War. Looked after by the CWGC, it differs from the stereotype in other ways too. It sits naturally in the folds of a rolling landscape with many mature trees and shrubs, and stone paths and steps leading from one group of gravestones to the next. It has a palpable sense of calm and reflection.

I was there a few days ago and it put me in mind of the sort of country churchyard that is so prevalent in this country. I’m not sure if it would ever be quite right to describe a cemetery as ‘intimate’, but Saint Symphorien comes close.

The Western Front

And I went because, on 4 August this year, it will be one of three sites where events will take place to mark the centenary of Britain’s entry to the war. Why that cemetery in particular? Because it has a particular aptness to the centenary, and not simply because it contains the graves of both sides in the war.

You’ll also find the grave of the first British casualty on the Western Front, John Parr. Private Parr, of the 4th Middlesex, has his age given on the gravestone as 20; in truth he, like many, probably concealed his true age and could, in fact, have been as much as four years younger than that. Coincidentally, his grave faces that of George Edwin Ellison, the last British soldier killed before the Armistice, who died just ten minutes before the end of hostilities on the Western Front.

War Diaries

Saint Symphorien contains so many stories, so it seems to me to be an entirely fitting place to mark the first day of the centenary. The four years that follow will give us all, young and old, a chance to hear those stories, remember and reflect on those terrible sacrifices that were made for each and every one of us at that time.

It’s stories, of course, that help to bring historic events alive to those looking back on them from the perspective of a hundred years later. Historians and pundits have already been hard at work producing work, tied to the centenary, to describe and try to make sense of what happened during the build up to – and course of – the war. There’s absolutely no shortage of analysis on the what, where, when and why.

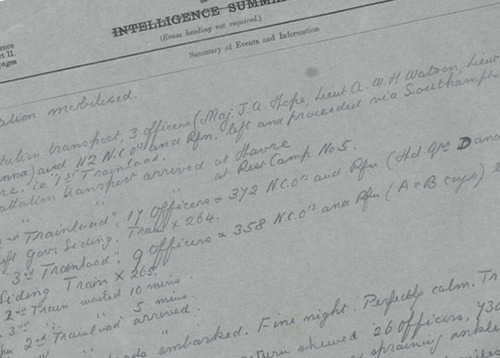

But it’s also good to see accounts of the war that were written at the time, from the soldiers and servicemen who took part. The National Archives has digitised 1.5 million pages of the war diaries and personal accounts kept by the combatants across the war, and will be putting them online over the months to come. The first selection provide a real-time account of the first three cavalry and the first seven infantry divisions who were part of the first wave of British army troops deployed in France and Flanders. The grim details of battle and the casualties that ensued are told with the unvarnished matter-of-factness that marks out the truly contemporary account.

Eggs, Potatoes and Jam

There are moments of lightness too. One officer describes a break in the fighting:

Find on arrival the interpreters have given us a very good meal. Bread, eggs, potatoes, and jam, with six “good bottles” as the French would say. Searched the farmhouse in which we fed and found a large washing-tub. All hands on to boil water and at 10pm a glorious bath. I was exceedingly dirty, I am sorry to say.

Allied to this work, the National Archives has also launched a crowdsourcing project using the war diaries. Operation War Diary, as it is called, wants volunteers to study diary entries and tag any data they find, whether it’s a person, place, or activity. The Archives have much basic information about the diaries – the units they relate to, and the date ranges – but beyond that they don’t know how many people are named in the diaries, or how much they can tell us about how the war was actually fought on the front line. If you can spare an hour or so of your time you can become part of this fascinating project yourself.

Medals in Sochi?

Finally, a quick word about the forthcoming Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games. You can hardly have missed the trailers on the TV, but what chance do Team GB have to get in the medals? Well, obviously we are not expecting to match the totals we reached two years ago in the London summer games, but our team are going in with heads held high.

Last week UK Sport announced the medal targets for Team GB and Paralympics GB for Sochi. For the Olympic team it’s to win at least three medals and for the Paralympic team it’s to win at least two. If we were to do that it would be our best performance at a Winter Games in generations. We will have a very strong British team out in Sochi supported by record amounts of public funding, with over £14 million invested. I know our athletes are raring to go. The whole country will be behind them and I look forward to being in Sochi to support the teams in person.

Department for Culture, Media and Sport

Department for Culture, Media and Sport